In collection-defense cases, I frequently see out-of-state defendants served by email, regular mail, or certified mail—methods that, absent a statute (e.g., CPLR 313, BCL § 307) or a court order under CPLR 308(5), generally require a written contractual waiver to confer personal jurisdiction in New York. While commercial entities such as Merchant Cash Advance companies sometimes use contractual service waivers to provide for alternative service methods, courts require proper authentication of these agreements. This case examines the requirements for establishing jurisdiction through contractually agreed-upon service methods.

Background of Case Studied

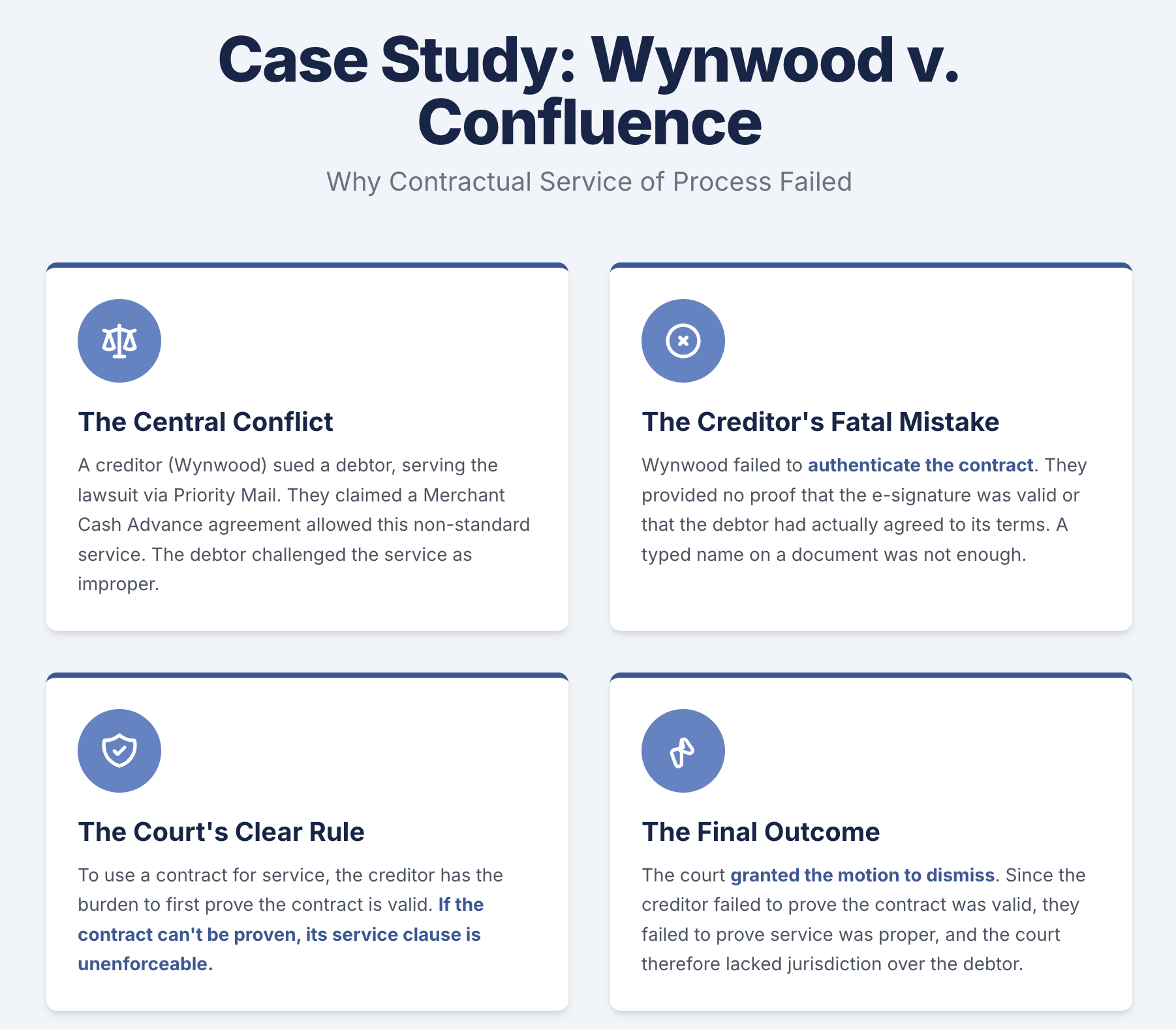

Wynwood Capital Group LLC (Plaintiff) initiated a lawsuit against Defendants for an alleged breach of contract involving the purchase of future receivables. The case was commenced on February 6, 2024, with the court issuing its decision on May 10, 2024.

The dispute centered on whether the service of process, conducted according to a contractual provision allowing service by Priority Mail, was sufficient to establish personal jurisdiction over the defendants.

Legal Issues Presented

The court was tasked with determining whether personal jurisdiction over the defendants could be obtained through a mode of service not provided for by statutory law but agreed upon in a contract. The defendants moved to dismiss the complaint, arguing lack of personal jurisdiction due to improper service.

Court’s Analysis

Contractual Agreement on Service of Process

The court examined the contractual provision that permitted service of process by Priority Mail. Historically, New York courts have upheld the validity of such agreements, allowing parties to establish alternate methods of service (see Gilbert v. Burnstine, 255 N.Y. 348, 354–55 (1931); Alfred E. Mann Living Tr. v. ETIRC Aviation S.A.R.L., 78 A.D.3d 137, 140 (N.Y. App. Div. 2010)).

Burden of Proof for Personal Jurisdiction

The plaintiff always carries the burden of persuasion on personal jurisdiction; what changes after the prima facie phase is the quantum of proof required (from prima facie to preponderance) and the court’s willingness to resolve factual conflicts. This involves demonstrating that service was performed in accordance with the agreed-upon method, provided the contract is valid (see Rockman v. Nassau County Sheriff’s Dep’t, 224 A.D.3d 758 (N.Y. App. Div. 2024); Shatara v. Ephraim, 137 A.D.3d 1248, 1249 (N.Y. App. Div. 2016)).

Validation of the Contract

For the plaintiff to rely on a contractual service provision, the contract itself must be authenticated. The plaintiff in this case failed to provide sufficient evidence to prove the validity of the “Standard Merchant Cash Advance Agreement,” which included the service provision (see AJ Equity Grp. LLC v. Off. Connection, Inc., 80 Misc. 3d 1233(A), 2023 N.Y. Slip Op. 51157(U) (Sup. Ct. 2023)).

Strict Compliance with Service Provisions

Even if parties contractually agree to an alternate method of service, the plaintiff must strictly comply with the terms of that agreement. The court found that the plaintiff did not meet this requirement, failing to establish that service by Priority Mail was executed as per the contractual terms (see Reserve Funding Grp. LLC v. JL Cap. Holdings LLC, 77 Misc. 3d 1221(A), 2022 N.Y. Slip Op. 51322(U) (Sup. Ct. 2022)).

Effect of Defendants' Actual Notice

Actual notice alone does not cure a defective mode of service unless the defendant makes a general appearance or otherwise waives the objection under CPLR 3211(e). Proper service, as stipulated by law or a valid contract, is necessary to establish jurisdiction, regardless of whether the defendants had actual notice of the action (see Emigrant Mortg. Co. v. Westervelt, 105 A.D.3d 896 (N.Y. App. Div. 2013)).

Conclusion

The court ultimately granted the defendants’ motion to dismiss for lack of personal jurisdiction, highlighting several critical points:

- Contractual parties can agree to alternative methods of service of process.

- The plaintiff must authenticate the contract and strictly comply with its terms.

- Actual notice of the legal action does not substitute for proper service.

![]() This decision underscores the importance of adhering to statutory and contractual requirements when serving process to ensure valid legal proceedings.

This decision underscores the importance of adhering to statutory and contractual requirements when serving process to ensure valid legal proceedings.

For assistance with service of process disputes or contractual service provisions, schedule a consultation with Jesse Langel, Esq., who practices in collection defense matters.

This case highlights the importance of adhering to contractual requirements to establish jurisdiction in legal proceedings. If you need help, complete this intake form.

For more about service, read Properly Notified of the Lawsuit?

Full Text of Wynwood Capital Group LLC v Confluence Corp.

Wynwood Capital Group LLC v Confluence Corp.

Index No. 503752/2024

Question Presented

Where a plaintiff claims that personal jurisdiction has been obtained over defendants through a mode of service of process not otherwise provided for in statutory law but contained within an agreement, does the court lack personal jurisdiction over the defendants where the plaintiff has failed to establish the bona fides of said agreement?

Background

This action was commenced on February 6, 2024, by Plaintiff Wynwood Capital Group LLC (Plaintiff), who allegedly purchased future receivables from Defendant Confluence Corporation d/b/a Regal Service Company (Corporate Defendant) pursuant to a contract (also referred to as agreement) which was guaranteed by Defendant Christopher William Caliedo (Individual Defendant). Plaintiff claims that Defendants breached the contract and owe $443,181.26 in undelivered future receivables. (See generally NYSCEF Doc No. 1, Complaint.)

Defendants answered the complaint on February 13, 2024. The only allegations of the complaint which Defendants admitted were those that asserted that Corporate Defendant was organized and existing under the laws of Hawaii and that Individual Defendant resides in Hawaii. (See NYSCEF Doc No. 3, Answer ¶ 2.)

In response to the complaint's allegation that "Venue is proper in this breach of contract claim, pursuant to the subject contract which contains a clause specifying that New York is the exclusive jurisdiction for all disputes arising under the contract" (NYSCEF Doc No. 1, complaint ¶ 4), Defendants alleged:

3. Defendants deny the allegations contained in Paragraph 4 of the complaint, specifically Defendants deny that the agreement and/or clause in the contract is valid on personal jurisdiction grounds as well as pursuant to GOL § 5-1402. Plaintiff does not have personal jurisdiction over the defendant. Without waiving objections, the plaintiff failed to obtain . . . personal jurisdiction over the defendant. To the extent a response is required, the Defendants deny the allegations and demand strict proof thereof. (NYSCEF Doc No. 3, answer ¶ 3.)

Moreover, Defendants' twenty-sixth affirmative defense asserted, "This Court has no jurisdiction over the person of defendant in that service of process was insufficient and not perfected under the applicable rules of the Civil Practice Law and Rules" (id. ¶ 31).

Defendants now move for an order pursuant to CPLR 3211 (a) (8) ("the court has not jurisdiction of the person of the defendant") dismissing the complaint and for such other and further relief as the Court deems proper.

Contentions

Defendants' counsel's affirmation in support of their motion to dismiss stated that their arguments were set forth in an accompanying memorandum of law (see NYSCEF Doc No. 10, Dale aff ¶ 4).

The thrust of Defendants' position is that "Plaintiff failed to establish service on the corporate defendant" as the New York Secretary of State was not served pursuant to Business Corporation Law § 307, and that "The plaintiff failed to properly serve the natural person defendant[ ]; either by personal service or substituted service" (NYSCEF Doc No. 11, mem law ¶ 3). The affidavit of service filed by Plaintiff was defective, argued Defendants (see id. ¶ 8). "Based upon the plaintiff's defective affidavit of compliance, the complaint must be dismissed for lack of personal jurisdiction over the corporate defendant" (id.). "Here, the plaintiff has not demonstrated that service was made upon the individual natural defendant[ ] herein pursuant to CPLR Sections 308, 312-a and 313. As such, the summons and complaint must be dismissed." (Id. ¶ 10.)

In opposition, Plaintiff adverts to the agreement which it claims forms the basis of this breach-of-contract action. The same agreement that embodied the parties' transaction of Plaintiff purchasing Corporate Defendant's accounts receivable also contained a paragraph whereby Corporate Defendant consented to service of process via first-class mail or Priority Mail:

Each Merchant and each Guarantor consent to service of process and legal notices made by First Class or Priority Mail delivered by the United States Postal Service and addressed to the Contact Address set forth on the first page of this Agreement or any other address(es) provided in writing to WCG by any Merchant or any Guarantor, and unless applicable law or rules provide otherwise, any such service will be deemed complete upon dispatch. Each Merchant and each Guarantor also consent to service of process and legal notices made by e-mail to the E-mail Address set forth on the first page of this Agreement or any other e-mail address(es) provided in writing to WCG by any Merchant or any Guarantor, and unless applicable law or rules provide otherwise, any such service will be deemed complete upon dispatch. Each Merchant and each Guarantor agrees that it will be precluded from asserting that it did not receive service of process or any other notice mailed to the Contact Address set forth on the first page of this Agreement or e-mailed to the E-mail Address set forth on the first page of this Agreement if it does not furnish a certified mail return receipt signed by WCG demonstrating that WCG was provided with notice of a change in the Contact Address or the Email Address. (NYSCEF Doc No. 13, Pretter aff ¶ 11, quoting NYSCEF Doc No. 14, agreement ¶ 43.)

Plaintiff also adverted to Individual Defendant's guarantee of Corporate Defendant's compliance with the contract, which included a similar provision agreeing to service of process via first-class mail or Priority Mail:

Each Merchant and each Guarantor consent to service of process and legal notices made by First Class or Priority Mail delivered by the United States Postal Service and addressed to the Contact Address set forth on the first page of the Agreement or any other address(es) provided in writing to WCG by any Merchant or any Guarantor, and unless applicable law or rules provide otherwise, any such service will be deemed complete [*2]upon dispatch. Each Merchant and each Guarantor also consent to service of process and legal notices made by e-mail to the E-mail Address set forth on the first page of this Agreement or any other e-mail address(es) provided in writing to WCG by any Merchant or any Guarantor, and unless applicable law or rules provide otherwise, any such service will be deemed complete upon dispatch. Each Merchant and each Guarantor agrees that it will be precluded from asserting that it did not receive service of process or any other notice mailed to the Contact Address set forth on the first page of the Agreement or e-mailed to the E-mail Address set forth on the first page of the Agreement if it does not furnish a certified mail return receipt signed by WCG demonstrating that WCG was provided with notice of a change in the Contact Address or the Email Address. (NYSCEF Doc No. 13, Pretter aff ¶ 11, quoting NYSCEF Doc No. 14, agreement ¶ G14.[FN1])

Pointing to case law which sanctions the ability of parties to circumvent statutory provisions governing service of process by contractually agreeing to alternate methods, Plaintiff argues that an affirmation of service appended as Exhibit 2 attested to service of process by Priority Mail (see id., citing NYSCEF Doc No. 15, aff serv). Dated February 6, 2024 and executed by Attorney Isaac H. Greenfield, the affirmation of service provides in pertinent part:

I am the attorney for Plaintiff, am over the age of 18 years, am not a party to this action, and am a resident of the State of New York. On February 6, 2024, I served the within Summons and Complaint by delivering to Defendants via Priority Mail, pursuant to Section 43 of the Standard Merchant Cash Advance Agreement entered into between the Parties, a copy of the Summons and Verified Complaint, to the address(es) below (the priority mailing labels are annexed hereto for the Court's reference).

Therefore, concludes Plaintiff — who added that since Defendants filed an answer they obviously were served with the summons and complaint — Defendants' motion to dismiss pursuant to CPLR 3211 (a) (8) should be dismissed (see NYSCEF Doc No. 13, Pretter aff ¶¶ 18-20).

Discussion — Law

The burden of proving that personal jurisdiction has been acquired over a defendant in an action rests with the plaintiff (see Rockman v Nassau County Sheriff's Dept., 224 AD3d 758 [2d Dept 2024]). "[T]o defeat a CPLR 3211 (a) (8) motion to dismiss a complaint, the plaintiff need only make a prima facie showing that the defendant is subject to the personal jurisdiction of the court" (Shatara v Ephraim, 137 AD3d 1248, 1249 [2d Dept 2016]).

The process delineated for serving an unauthorized foreign corporation in a New York Court and the consequences of failing to comply with that process have been well described as follows:

"Business Corporation Law § 307 establishes a mandatory sequence and progression of [*3]service completion options to acquire jurisdiction over a foreign corporation not authorized to do business in New York" (Stewart v Volkswagen of Am., 81 NY2d 203, 207 [1993]). First, process must be personally served upon the Secretary of State in the City of Albany or his or her deputy or authorized agent for service (see Business Corporation Law § 307 [b]).[FN2] Then, as is relevant here, notice of the service and a copy of the process must be "[s]ent . . . to such foreign corporation by registered mail with return receipt requested, at the post office address specified for the purpose of mailing process, on file in the department of state . . . in the jurisdiction of its incorporation, or if no such address is there specified, to its registered or other office there specified, or if no such office is there specified, to the last [known] address of such foreign corporation" (Business Corporation Law § 307 [b] [2]). Finally, an affidavit of compliance, together with the process and the return receipt or other official proof of delivery, must be filed with the clerk of the court within a specified time period (see Business Corporation Law § 307 [c] [2]). Service is not deemed complete until 10 days after such papers are filed (see Business Corporation Law § 307 [c] [2]; see also Flick v Stewart-Warner Corp., 76 NY2d 50, 55 [1990]).

The Court of Appeals has made clear that the "precisely . . . delineated sequence set forth in the statute" compels a plaintiff to proceed in a "strict sequential pattern" and that the failure to do so is a jurisdictional defect requiring dismissal (Stewart v Volkswagen of Am., 81 NY2d at 208; see Flick v Stewart-Warner Corp., 76 NY2d at 57; see also Issing v Madison Sq. Garden Ctr., Inc., 62 AD3d 407 [2009]; Reed v Gowanda Nursing Home, 5 AD3d 987 [2004], affd 4 NY3d 770 [2005]). Further, the failure to file an affidavit of compliance is also a jurisdictional defect (see Flannery v General Motors Corp., 86 NY2d 771, 773 [1995]; Smolen v Cosco, Inc., 207 AD2d 441 [1994]).

Here, plaintiffs failed to sustain their burden of proving that the statutory requirements for jurisdiction were satisfied (see Matter of Country Side Sand & Gravel Inc. v Town of Pomfret Zoning Bd. of Appeals, 57 AD3d 1501, 1502 [2008], lv denied 61 AD3d 1439 [2009]). The affidavit of service contained in the record only establishes personal service upon the Secretary of State; it is silent as to any attempt to serve defendant in accordance with Business Corporation Law § 307. Nor did plaintiffs mail the required notice and process to the registered office address for defendant on file with the applicable department of state by registered mail as statutorily required. Instead, deeming the registered office address to be incomplete, plaintiffs' process server mailed the notice and process to a different address listed for defendant's corporate officers via certified mail, return receipt requested.[ ] Although the record contains an unsigned notice purporting to establish that a copy of the summons and complaint was mailed to defendant, in light of the strict and specific statutory requirements, such notice is insufficient to constitute an affidavit of compliance—particularly when it erroneously recites that process was served by registered mail. Having failed to comply with the strict requirements of Business Corporation Law § 307, plaintiffs did not obtain jurisdiction over defendant and the motion to dismiss should have been granted. (VanNorden v Mann Edge Tool Co., 77 [*4]AD3d 1157, 1158-1159 [3d Dept 2010].)

It is undisputed that neither Defendant was served with the summons and complaint in a manner prescribed by statutory law. Corporate Defendant was not served in accordance with Business Corporation Law § 307, and Individual Defendant was not served as per the CPLR's provisions for serving a natural person (e.g., CPLR 308 [personal service within state], 312-a personal service by mail], 313 [person service without state]).

Rather, resolution of Defendants' motion depends upon whether the alleged agreement provided a basis for valid service and whether Plaintiff established that service of the summons and complaint complied with the allegedly agreed-upon contractual provisions.

Over many years, New York courts have sustained the rights of contractual parties to establish modalities of service of process alternative to those prescribed in statute. In Gilbert v Burnstine (255 NY 348 [1930]), the Court of Appeals was presented with the issue of a service provision in a contract providing for the sale by New York residents of zinc concentrates to the plaintiff. Differences were to be arbitrated in London. The plaintiff served process in New York upon the defendants, directing them to appear in London. The defendants argued that the British court could not acquire jurisdiction over them in the absence of personal service upon them within Great Britain. In finding that British jurisdiction had been acquired over the defendants, the Court reasoned:

Contracts made by mature men who are not wards of the court should, in the absence of potent objection, be enforced. Pretexts to evade them should not be sought. Few arguments can exist based on reason or justice or common morality which can be invoked for the interference with the compulsory performance of agreements which have been freely made. Courts should endeavor to keep the law at a grade at least as high as the standards of ordinary ethics. Unless individuals run foul of constitutions, statutes, decisions or the rules of public morality, why should they not be allowed to contract as they please? Our government is not so paternalistic as to prevent them. Unless their stipulations have a tendency to entangle national or state affairs, their contracts in advance to submit to the process of foreign tribunals partake of their strictly private business. Our courts are not interested except to the extent of preserving the right to prevent repudiation. In many instances problems not dissimilar from the one presented by this case have been solved. Vigor has been infused into process otherwise impotent. Consent is the factor which imparts power. (Id. at 354-355.)

Quoting from a treatise, the Court of Appeals wrote,

Jurisdiction over the person of the defendant may be acquired by his consent. The consent may be given either before or after action has been brought. Jurisdiction is conferred when the defendant enters a general appearance in an action, that is, an appearance for some purpose other than that of raising the objection of lack of jurisdiction over him. A stipulation waiving service has the same effect. The defendant may, before suit is brought, give a power of attorney to confess judgment or appoint an agent to accept service, or agree that service by any other method shall be sufficient. (Id. at 355 [emphasis added].)

The Court also quoted from Pennoyer v Neff (95 US 714, 735 [1877]), as follows: "It is not contrary to natural justice that a man who has agreed to receive a particular mode of notification of legal proceedings should be bound by a judgment in which that particular mode of notification has been followed, even though he may not have actual notice of them" (Gilbert, 255 NY at 355-356). Therefore, Gilbert established the proposition in New York law that a party who has acquiesced to jurisdiction through a validly executed agreement may not avoid the consequences of the results of the litigation.

Decades later, in a case entitled National Equip. Rental v Dec-Wood Corp. (49 Misc 2d 538 [Dist. Ct, Nassau County 1966]), the trial court held that service of the summons by certified mail, as per a leasing agreement between the parties, was contrary to any of the methods authorized by the Civil Practice Law and Rules. "The service of process being a matter of procedure, which the Constitution has relegated to the Legislature, the parties may not, by private agreement, provide for other or alternate ways of service. They are bound to follow one of the methods designated in the Civil Practice Laws and Rules, and no other." (Id. at 540.) Citing to Gilbert, the Appellate Term reversed, holding, "It was error to deny the motion on the ground that in personam jurisdiction of the defendants had not been acquired. Defendants had by prior written agreement submitted to the jurisdiction of the courts of this State and were served with process by certified mail—return receipt requested—in accordance with the terms of that agreement. Such service was sufficient and effectively conferred jurisdiction over the defendants." (National Equip. Rental v Dec-Wood Corp., 51 Misc 2d 999, 1000 [App Term, 2d Dept 1966].)

Decades later, in an age where much communication is effected virtually through email, the Court in Alfred E. Mann Living Trust v ETIRC Aviation S.A.R.L. (78 AD3d 137 [1st Dept 2010]) upheld service by that method. "The comprehensive consent to jurisdiction, waiver of personal service, and waiver of any objection to lack of personal jurisdiction contained in the guaranty precludes a viable challenge to the court's jurisdiction over plaintiff's CPLR 3213 motion against Pieper. . . . Pieper, by contrast, expressly waived, in writing, any right to formal service of process in an action under his guaranty." (Id. at 139-140.) In so concluding, the Appellate Division went as far as to hold that the service provisions of the Hague Convention (Hague Convention on the Service Abroad of Judicial and Extrajudicial Documents in Civil or Commercial Matters, 20 UST 361, TIAS No. 6638 [1965]) could even be waived through contractual agreement. The Court's recitation of the case law on the topic included references to cases discussed hereinabove:

Pieper cannot dispute that parties to a contract are free to contractually waive service of process (see e.g. Comprehensive Merchandising Catalogs, Inc. v Madison Sales Corp., 521 F2d 1210, 1212 [7th Cir 1975]; National Equip. Rental v DecWood Corp., 51 Misc 2d 999 [App Term 1966]; see generally 86 NY Jur 2d, Process and Papers § 7). By definition, such waivers render inapplicable the statutes that normally direct and limit the acceptable means of serving process on a defendant. Indeed, a stipulation waiving service confers jurisdiction, precluding the defendant from successfully challenging the court's jurisdiction over him: "Jurisdiction over the person of the defendant may be acquired by his consent" (Gilbert v Burnstine, 255 NY 348, 355 [1931] [internal quotation marks and citation omitted]), and jurisdiction is conferred by a stipulation waiving service (id.). (Alfred E. Mann Living Trust, 78 AD3d at 140.)

Confirming that case law continued to permit alternate means of service of process, the court in People by Schneiderman v Northern Leasing Systems, Inc. (60 Misc 3d 867, 879 [Sup Ct, NY County 2017], affd 169 AD3d 527 [1st Dept 2019] [action alleging fraudulent business practices by companies leasing out credit card processing machines]) wrote:

Contracting parties may agree to means of service alternative to the statutorily required means. The typical leases that the Northern Leasing respondents present, on which petitioners may rely to oppose dismissal . . . permit service of process commencing litigation of claims under the leases by mail to the mailing address in the lease or to the lessee's or guarantor's current or last known address when the litigation is commenced. Alternative means of service to which contracting parties freely agree are also enforceable. (Knopf v Sanford, 150 AD3d 608, 610 [1st Dept 2017]; Alfred E. Mann Living Trust v ETIRC Aviation S.A.R.L., 78 AD3d 137, 141 [1st Dept 2010]; Clovine Assoc. Ltd. Partnership v Kindlund, 211 AD2d 572, 573 [1st Dept 1995]; Credit Car Leasing Corp. v Elan Group Corp., 185 AD2d 109, 109 [1st Dept 1992].) Even agreed upon waivers of service are enforceable. (Alfred E. Mann Living Trust v ETIRC Aviation S.A.R.L., 78 AD3d at 140.)

AJ Equity Group LLC v Office Connection, Inc (80 Misc 3d 1233[A], 2023 NY Slip Op 51157[U] [Sup Ct, Monroe County 2023]), involved a plaintiff's claim of the defendants' breach of a merchant cash advance contract which contained a service-by-regular mail provision. The court spend much of its discussion on the issue of whether an "e-signature" of a defendant, Karen Minc, was legitimate. The evidence was not conclusive. "The plaintiff does not provide an affidavit, or other admissible evidence, explaining the significance of the 'signature certificate' to allow this Court to determine, as a matter of law, that the agreement contains Ms. Minc's signature or that it constitutes valid acceptance of the contract" (id., 2023 NY Slip Op. 51157[U] at *3). Significant is the court's discussion of the issue of jurisdiction raised by Minc:

If plaintiff establishes that she did sign the agreement, as the agreement's terms dictated that the parties agreed on the New York jurisdiction provision and service by mail provision, those arguments are meritless. Parties are free to contractually waive the statutory rules regarding service of process. (See Alfred E. Mann Living Tr. v. ETIRC Aviation S.A.R.L., 78 AD3d 137, 140 [1st Dept. 2010]: ". . . parties to a contract are free to contractually waive service of process (see e.g. Comprehensive Merchandising Catalogs, Inc. v Madison Sales Corp., 521 F2d 1210, 1212 [7th Cir 1975]; National Equip. Rental v DecWood Corp., 51 Misc 2d 999 [App Term 1966]; see generally 86 NY Jur 2d, Process and Papers § 7). By definition, such waivers render inapplicable the statutes that normally direct and limit the acceptable means of serving process on a defendant.") (AJ Equity Group LLC, 2023 NY Slip Op. 51157 at *3-4 [emphasis added].)

It is notable that the court placed the burden on the plaintiff to establish whether defendant Minc signed the agreement.

In Reserve Funding Group LLC v JL Capital Holdings LLC (77 Misc 3d 1221[A], 2022 NY Slip Op 51322[U] [Sup Ct, Kings County 2022]), the court was faced with whether to vacate [*5]a default judgment entered by the County Clerk based upon non-response to service of process via certified mail, when the merchant cash advance contract provided for certified mail return receipt requested service. Since the plaintiff did not proffer return receipts it could not establish when the defendants were presumed to have received the summons and complaint. "Here, the plaintiff has not established that it acquired personal jurisdiction over the defendants" (id., 2022 NY Slip Op 51322[U] at *5), held the court, while acknowledging that

The plaintiff filed an affirmation of service attesting to service of the commencement papers on the defendants by certified mail in accordance [with] section 4.3 of a Revenue Purchase Agreement purportedly signed by the parties. Parties to a contract are free to contractually waive service of process; such waivers render inapplicable the statutes that normally direct and limit the acceptable means of serving process on a defendant (Alfred E. Mann Living Tr. v. ETIRC Aviation S.a.r.l., 78 AD3d 137 [1st Dept 2010]). The Court recognizes the right of contracting parties to waive the protections of statutory methods of service of process and to designate alternative methods of service. In the case at bar, the plaintiff contends that the defendants did exactly that and consented to service of the commencement papers by certified mail pursuant to the RPA. The defendants directly dispute this claim. (Id. at *2.)

From this decision we glean that if the parties do contract to a non-statutorily prescribed mode of service, it must be complied with strictly in order to gain personal jurisdiction over the defendants.

Based on the foregoing case law analysis, this Court holds that (a) contractual parties are free to mutually agree upon a method of service of process other than those provided for in statute, such as Business Corporation Law § 307 or CPLR provisions such as 308, 312-a and 313, (b) they may elect to subject themselves to service of process by a variety of means, such as regular (first-class) mail, certified mail, or certified mail return requested, or even the computer-era communication means of email, (3) the burden of proof on the issue of whether personal jurisdiction was acquired through service of process in accordance with a contractual provision lies with the plaintiff, (4) the contract must be proved to be valid in the first instance, and (5) service of process in reliance upon a contractual provision must have been effectuated strictly in accordance therewith.

Discussion — Application of Facts

Plaintiff submitted a contract entitled "Standard Merchant Cash Advance Agreement" dated December 13, 2023 ("December 13, 2023 Agreement"). It purported to constitute an agreement between Plaintiff and Corporate Defendant to purchase $596,000.00 of the latter's receivables for a purchase price of $400,000.00 to be paid by the former. Annexed was a "Guarantee" in which Individual Defendant purportedly obligated himself to guarantee Corporate Defendant's performance of all representations, warranties, and covenants. (See generally NYSCEF Doc No. 14, agreement.)

It is undenied by Plaintiff that service of the summons and complaint in this action did not take place in accordance with statutorily prescribed modes of service (see NYSCEF Doc No. 15, aff serv). That would support Defendants' claim of lack of personal jurisdiction. At oral [*6]argument, Plaintiff conceded such, but maintained that it was relying on the contractually prescribed methods of service. Service of process in accordance with the Agreement would be valid under case law since it was performed strictly in compliance with paragraphs 43 and G14 via Priority Mail, as permitted, and parties are free to mutually agree upon a method of service of process other than those provided for in statute (see supra at 6-9). Of course, that would depend on whether the Agreement was a valid one.

The December 13, 2023 Agreement is alleged by the Plaintiff in the complaint to have been entered into by the parties (see NYSCEF Doc No. 1, complaint ¶ 5), but this was denied by Defendant in their Answer, who alleged in pertinent part, "Defendants deny the allegations contained in Paragraph 5-13 of the complaint as same require legal conclusions to which no response is required. . . . To the extent a response is required, the Defendants deny the allegations and demand strict proof thereof." (NYSCEF Doc No. 3, answer ¶ 4.)

Since Plaintiff relies on paragraphs 43 and G14 of the December 13, 2023 Agreement as the contractual predicate for service of process via Priority Mail, and Defendants denied the said Agreement's validity, Plaintiff bore the burden of establishing the Agreement's bona fides in order to successfully oppose Defendant's motion to dismiss for lack of personal jurisdiction.

" '[T]he burden of proving the existence, terms and validity of a contract rests on the party seeking to enforce it' (Paz v Singer Co., 151 AD2d 234, 235 [1989]; see Sardis v Frankel, 113 AD3d 135, 143 [2014]; Silber v New York Life Ins. Co., 92 AD3d 436, 439 [2012]; Verizon NY, Inc. v Barlam Constr. Corp., 90 AD3d 1537, 1538 [2011]; DeLeonardis v County of Westchester, 35 AD3d 524, 526 [2006])" (Amica Mut. Ins. Co. v Kingston Oil Supply Corp., 134 AD3d 750, 752 [2d Dept 2015]). "This requires, in the first instance, authentication of the purported writing (see Clarke v American Truck & Trailer, Inc., 171 AD3d 405, 406 [1st Dept 2019]; Bermudez v Ruiz, 185 AD2d 212, 214 [1st Dept 1992]; see generally Prince, Richardson on Evidence § 9-101). Authentication may be effected by various means, including, for example, by certificate of acknowledgment (see CPLR 4538), by comparison of handwriting (see CPLR 4536), or by the testimony of a person who witnessed the signing of the document (see Andreyeva v Haym Solomon Home for the Aged, LLC, 190 AD3d 801, 802 [2d Dept 2021])." (Knight v New York & Presbyt. Hosp., 219 AD3d 75, 78 [1st Dept 2023].)

This Court notes that the December 13, 2023 Agreement bears an identical computer script typeface name of "Christopher Caliedo" at the bottom of pages 1, 11, 15, 16, and 17 (see NYSCEF Doc No. 14, agreement [deeming unnumbered pages to continue numbering past page 11]). Plaintiff did not submit an affidavit from someone with personal knowledge to establish that the December 13, 2023 Agreement in fact is an authentic and valid contract between it and Defendants, despite Defendants having denied the validity of this document in their answer. Nothing from Plaintiff establishes that the computer script typeface name of "Christopher Caliedo" reflects his signature and acquiescence to the purported agreement's contents (see AJ Equity Group LLC, 2023 NY Slip Op 51157[U]). Therefore, Plaintiff did not prove the validity of the December 13, 2023 Agreement.

Moreover, nothing from Plaintiff established the December 13, 2023 Agreement as a business record. As was held in Knight,

Dewitt's contention that the agreements are admissible as business records is unavailing. To have a document admitted as a business record, the party offering the record must show (1) it was produced in the ordinary course of business; (2) it was the regular course [*7]of business to make such record; and (3) it was made at the time of the act, transaction, occurrence or event or within a reasonable time thereafter (see CPLR 4518 [a]; People v Cratsley, 86 NY2d 81, 89 [1995]). In her supporting affidavit, Trimarchi states only that she conducted a search of Dewitt's records relating to decedent's admissions to Dewitt, and that she attached "true and complete" copies of those agreements as "kept and maintained . . . by [Dewitt] as a business record." In particular, Trimarchi does not aver that the agreements were not only maintained, but created, in the regular course of business (see People v Kennedy, 68 NY2d 569, 579 [1986]; JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A. v Clancy, 117 AD3d 472, 472 [1st Dept 2014]). Trimarchi's conclusory assertions do not meet what is required for admission of the agreements as business records. (Knight, 219 AD3d at 79-80.)

In opposing Defendants' motion to dismiss on the ground of lack of personal jurisdiction, Plaintiff relied solely on the affirmation of its counsel, who does not evince personal knowledge of the circumstances under which the December 13, 2023 Agreement was purportedly executed. Nothing establishes the Agreement as a business record exception to the hearsay rule (see CPLR 4518 [a]).

Closer to the point of jurisdiction, Knight contains the following discussion concerning a contractual forum selection clause, which is a related topic: "If the entire agreement is void, any forum selection clause contained therein is unenforceable (DeSola Group v Coors Brewing Co., 199 AD2d 141, 141-142 [1st Dept 1993]; see Lei Chen v Cenntro Elec. Group Ltd., 2023 WL 2752200, *3-4, 2023 US Dist LEXIS 57113, *6-7 [SD NY, Mar. 31, 2023, 22-CV-7760 (VEC)] [applying New York law])" (Knight, 219 AD3d at 80).

Therefore, without authentication of the December 13, 2023 Agreement in any manner permitted by law, it stands alone in a vacuum without probative value in terms of Plaintiff's reliance on it to justify serving Defendants by Priority Mail. Priority Mail not being a mode of service permitted by any of the heretofore discussed provisions of the CPLR or the Business Corporation Law, Plaintiff failed to meet its prima facie burden of proving that it acquired personal jurisdiction over Defendants (see Rockman, 224 AD3d 758; Shatara, 137 AD3d 1248; AJ Equity Group LLC, 2023 NY Slip Op 51157[U]); Reserve Funding Group LLC, 2022 NY Slip Op 51322[U]). Corporate Defendant was not served pursuant to Business Corporation Law § 307. Individual Defendant was not served pursuant to CPLR 308, 312-a, or 313.

Finally, it is noted that a defect in service is not cured by the defendant's subsequent receipt of actual notice of the commencement of the action (see Emigrant Mtge. Co., Inc. v Westervelt, 105 AD3d 896 [2d Dept 2013]). Hence, this Court rejects Plaintiff's argument that how Defendants were served is irrelevant since they concededly received the summons and complaint, as evidenced by their interposition of an answer.

Conclusion

Accordingly, IT IS HEREBY ORDERED that Defendants' motion to dismiss the within action for lack of personal jurisdiction pursuant to CPLR 3211 (a) (8) is GRANTED. The within complaint is dismissed, and the County Clerk shall enter judgment accordingly.